Collision detection

Collision detection typically refers to the computational problem of detecting the intersection of two or more objects. While the topic is most often associated with its use in video games and other physical simulations, it also has applications in robotics. In addition to determining whether two objects have collided, collision detection systems may also calculate time of impact (TOI), and report a contact manifold (the set of intersecting points).[1] Collision response deals with simulating what happens when a collision is detected (see physics engine, ragdoll physics). Solving collision detection problems requires extensive use of concepts from linear algebra and computational geometry.

Contents |

Overview

In physical simulation, we wish to conduct experiments, such as playing billiards. The physics of bouncing billiard balls are well understood, under the umbrella of rigid body motion and elastic collisions. An initial description of the situation would be given, with a very precise physical description of the billiard table and balls, as well as initial positions of all the balls. Given a force applied to the cue ball (probably resulting from a player hitting the ball with his or her cue stick), we want to calculate the trajectories, precise motion, and eventual resting places of all the balls with a computer program. A program to simulate this game would consist of several portions, one of which would be responsible for calculating the precise impacts between the billiard balls. This particular example also turns out to be numerically unstable: a small error in any calculation will cause drastic changes in the final position of the billiard balls.

Video games have similar requirements, with some crucial differences. While physical simulation needs to simulate real-world physics as precisely as possible, video games need to simulate real-world physics in an acceptable way, in real time and robustly. Compromises are allowed, so long as the resulting simulation is satisfying to the game players.

Collision detection in physical simulation

Physical simulators differ in the way they react on a collision. Some use the softness of the material to calculate a force, which will resolve the collision in the following time steps like it is in reality. Due to the low softness of some materials this is very CPU intensive. Some simulators estimate the time of collision by linear interpolation, roll back the simulation, and calculate the collision by the more abstract methods of conservation laws.

Some iterate the linear interpolation (Newton's method) to calculate the time of collision with a much higher precision than the rest of the simulation. Collision detection utilizes time coherence to allow even finer time steps without much increasing CPU demand, such as in air traffic control.

After an inelastic collision, special states of sliding and resting can occur and, for example, the Open Dynamics Engine uses constraints to simulate them. Constraints avoid inertia and thus instability. Implementation of rest by means of a scene graph avoids drift.

In other words, physical simulators usually function one of two ways, where the collision is detected a posteriori (after the collision occurs) or a priori (before the collision occurs). In addition to the a posteriori and a priori distinction, almost all modern collision detection algorithms are broken into a hierarchy of algorithms. Often the terms "discrete" and "continuous" are used rather than a posteriori and a priori.

A posteriori (discrete) versus a priori (continuous)

In the a posteriori case, we advance the physical simulation by a small time step, then check if any objects are intersecting, or are somehow so close to each other that we deem them to be intersecting. At each simulation step, a list of all intersecting bodies is created, and the positions and trajectories of these objects are somehow "fixed" to account for the collision. We say that this method is a posteriori because we typically miss the actual instant of collision, and only catch the collision after it has actually happened.

In the a priori methods, we write a collision detection algorithm which will be able to predict very precisely the trajectories of the physical bodies. The instants of collision are calculated with high precision, and the physical bodies never actually interpenetrate. We call this a priori because we calculate the instants of collision before we update the configuration of the physical bodies.

The main benefits of the a posteriori methods are as follows. In this case, the collision detection algorithm need not be aware of the myriad physical variables; a simple list of physical bodies is fed to the algorithm, and the program returns a list of intersecting bodies. The collision detection algorithm doesn't need to understand friction, elastic collisions, or worse, nonelastic collisions and deformable bodies. In addition, the a posteriori algorithms are in effect one dimension simpler than the a priori algorithms. Indeed, an a priori algorithm must deal with the time variable, which is absent from the a posteriori problem.

On the other hand, a posteriori algorithms cause problems in the "fixing" step, where intersections (which aren't physically correct) need to be corrected. Moreover, if the discrete step is not related to objects relative speed, the collision could go undetected, resulting in an object which passes through another, if fast enough.

The benefits of the a priori algorithms are increased fidelity and stability. It is difficult (but not completely impossible) to separate the physical simulation from the collision detection algorithm. However, in all but the simplest cases, the problem of determining ahead of time when two bodies will collide (given some initial data) has no closed form solution—a numerical root finder is usually involved.

Some objects are in resting contact, that is, in collision, but neither bouncing off, nor interpenetrating, such as a vase resting on a table. In all cases, resting contact requires special treatment: If two objects collide (a posteriori) or slide (a priori) and their relative motion is below a threshold, friction becomes stiction and both objects are arranged in the same branch of the scene graph

Optimization

The obvious approaches to collision detection for multiple objects are very slow. Checking every object against every other object will, of course, work, but is too inefficient to be used when the number of objects is at all large. Checking objects with complex geometry against each other in the obvious way, by checking each face against each other face, is itself quite slow. Thus, considerable research has been applied to speeding up the problem.

Exploiting temporal coherence

In many applications, the configuration of physical bodies from one time step to the next changes very little. Many of the objects may not move at all. Algorithms have been designed so that the calculations done in a preceding time step can be reused in the current time step, resulting in faster algorithms.

At the coarse level of collision detection, the objective is to find pairs of objects which might potentially intersect. Those pairs will require further analysis. An early high performance algorithm for this was developed by Ming C. Lin at the University of California, Berkeley [1], who suggested using axis-aligned bounding boxes for all n bodies in the scene.

Each box is represented by the product of three intervals (i.e., a box would be ![I_1 \times I_2 \times I_3=[a_1,b_1] \times [a_2,b_2] \times [a_3,b_3]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1f371e2f64c44695e65b9c0c22f1c682.png) .) A common algorithm for collision detection of bounding boxes is sweep and prune. We observe that two such boxes,

.) A common algorithm for collision detection of bounding boxes is sweep and prune. We observe that two such boxes,  and

and  intersect if, and only if,

intersect if, and only if,  intersects

intersects  ,

,  intersects

intersects  and

and  intersects

intersects  . We suppose that, from one time step to the next,

. We suppose that, from one time step to the next,  and

and  intersect, then it is very likely that at the next time step, they will still intersect. Likewise, if they did not intersect in the previous time step, then they are very likely to continue not to.

intersect, then it is very likely that at the next time step, they will still intersect. Likewise, if they did not intersect in the previous time step, then they are very likely to continue not to.

So we reduce the problem to that of tracking, from frame to frame, which intervals do intersect. We have three lists of intervals (one for each axis) and all lists are the same length (since each list has length  , the number of bounding boxes.) In each list, each interval is allowed to intersect all other intervals in the list. So for each list, we will have an

, the number of bounding boxes.) In each list, each interval is allowed to intersect all other intervals in the list. So for each list, we will have an  matrix

matrix  of zeroes and ones:

of zeroes and ones:  is 1 if intervals

is 1 if intervals  and

and  intersect, and 0 if they do not intersect.

intersect, and 0 if they do not intersect.

By our assumption, the matrix  associated to a list of intervals will remain essentially unchanged from one time step to the next. To exploit this, the list of intervals is actually maintained as a list of labeled endpoints. Each element of the list has the coordinate of an endpoint of an interval, as well as a unique integer identifying that interval. Then, we sort the list by coordinates, and update the matrix

associated to a list of intervals will remain essentially unchanged from one time step to the next. To exploit this, the list of intervals is actually maintained as a list of labeled endpoints. Each element of the list has the coordinate of an endpoint of an interval, as well as a unique integer identifying that interval. Then, we sort the list by coordinates, and update the matrix  as we go. It's not so hard to believe that this algorithm will work relatively quickly if indeed the configuration of bounding boxes does not change significantly from one time step to the next.

as we go. It's not so hard to believe that this algorithm will work relatively quickly if indeed the configuration of bounding boxes does not change significantly from one time step to the next.

In the case of deformable bodies such as cloth simulation, it may not be possible to use a more specific pairwise pruning algorithm as discussed below, and an n-body pruning algorithm is the best that can be done.

If an upper bound can be placed on the velocity of the physical bodies in a scene, then pairs of objects can be pruned based on their initial distance and the size of the time step.

Pairwise pruning

Once we've selected a pair of physical bodies for further investigation, we need to check for collisions more carefully. However, in many applications, individual objects (if they are not too deformable) are described by a set of smaller primitives, mainly triangles. So now, we have two sets of triangles,  and

and  (for simplicity, we will assume that each set has the same number of triangles.)

(for simplicity, we will assume that each set has the same number of triangles.)

The obvious thing to do is to check all triangles  against all triangles

against all triangles  for collisions, but this involves

for collisions, but this involves  comparisons, which is highly inefficient. If possible, it is desirable to use a pruning algorithm to reduce the number of pairs of triangles we need to check.

comparisons, which is highly inefficient. If possible, it is desirable to use a pruning algorithm to reduce the number of pairs of triangles we need to check.

The most widely used family of algorithms is known as the hierarchical bounding volumes method. As a preprocessing step, for each object (in our example,  and

and  ) we will calculate a hierarchy of bounding volumes. Then, at each time step, when we need to check for collisions between

) we will calculate a hierarchy of bounding volumes. Then, at each time step, when we need to check for collisions between  and

and  , the hierarchical bounding volumes are used to reduce the number of pairs of triangles under consideration. For simplicity, we will give an example using bounding spheres, although it has been noted that spheres are undesirable in many cases.

, the hierarchical bounding volumes are used to reduce the number of pairs of triangles under consideration. For simplicity, we will give an example using bounding spheres, although it has been noted that spheres are undesirable in many cases.

If  is a set of triangles, we can precalculate a bounding sphere

is a set of triangles, we can precalculate a bounding sphere  . There are many ways of choosing

. There are many ways of choosing  , we only assume that

, we only assume that  is a sphere that completely contains

is a sphere that completely contains  and is as small as possible.

and is as small as possible.

Ahead of time, we can compute  and

and  . Clearly, if these two spheres do not intersect (and that is very easy to test), then neither do

. Clearly, if these two spheres do not intersect (and that is very easy to test), then neither do  and

and  . This is not much better than an n-body pruning algorithm, however.

. This is not much better than an n-body pruning algorithm, however.

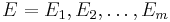

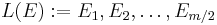

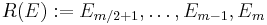

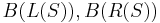

If  is a set of triangles, then we can split it into two halves

is a set of triangles, then we can split it into two halves  and

and  . We can do this to

. We can do this to  and

and  , and we can calculate (ahead of time) the bounding spheres

, and we can calculate (ahead of time) the bounding spheres  and

and  . The hope here is that these bounding spheres are much smaller than

. The hope here is that these bounding spheres are much smaller than  and

and  . And, if, for instance,

. And, if, for instance,  and

and  do not intersect, then there is no sense in checking any triangle in

do not intersect, then there is no sense in checking any triangle in  against any triangle in

against any triangle in  .

.

As a precomputation, we can take each physical body (represented by a set of triangles) and recursively decompose it into a binary tree, where each node  represents a set of triangles, and its two children represent

represents a set of triangles, and its two children represent  and

and  . At each node in the tree, we can precompute the bounding sphere

. At each node in the tree, we can precompute the bounding sphere  .

.

When the time comes for testing a pair of objects for collision, their bounding sphere tree can be used to eliminate many pairs of triangles.

Many variants of the algorithms are obtained by choosing something other than a sphere for  . If one chooses axis-aligned bounding boxes, one gets AABBTrees. Oriented bounding box trees are called OBBTrees. Some trees are easier to update if the underlying object changes. Some trees can accommodate higher order primitives such as splines instead of simple triangles.

. If one chooses axis-aligned bounding boxes, one gets AABBTrees. Oriented bounding box trees are called OBBTrees. Some trees are easier to update if the underlying object changes. Some trees can accommodate higher order primitives such as splines instead of simple triangles.

Exact pairwise collision detection

Once we're done pruning, we are left with a number of candidate pairs to check for exact collision detection.

A basic observation is that for any two convex objects which are disjoint, one can find a plane in space so that one object lies completely on one side of that plane, and the other object lies on the opposite side of that plane. This allows the development of very fast collision detection algorithms for convex objects.

Early work in this area involved "separating plane" methods. Two triangles collide essentially only when they can not be separated by a plane going through three vertices. That is, if the triangles are  and

and  where each

where each  is a vector in

is a vector in  , then we can take three vertices,

, then we can take three vertices,  , find a plane going through all three vertices, and check to see if this is a separating plane. If any such plane is a separating plane, then the triangles are deemed to be disjoint. On the other hand, if none of these planes are separating planes, then the triangles are deemed to intersect. There are twenty such planes.

, find a plane going through all three vertices, and check to see if this is a separating plane. If any such plane is a separating plane, then the triangles are deemed to be disjoint. On the other hand, if none of these planes are separating planes, then the triangles are deemed to intersect. There are twenty such planes.

If the triangles are coplanar, this test is not entirely successful. One can add some extra planes, for instance, planes that are normal to triangle edges, to fix the problem entirely. In other cases, objects that meet at a flat face must necessarily also meet at an angle elsewhere, hence the overall collision detection will be able to find the collision.

Better methods have since been developed. Very fast algorithms are available for finding the closest points on the surface of two convex polyhedral objects. Early work by Ming C. Lin[2] used a variation on the simplex algorithm from linear programming. The Gilbert-Johnson-Keerthi distance algorithm has superseded that approach. These algorithms approach constant time when applied repeatedly to pairs of stationary or slow-moving objects, when used with starting points from the previous collision check.

The end result of all this algorithmic work is that collision detection can be done efficiently for thousands of moving objects in real time on typical personal computers and game consoles.

A priori pruning

Where most of the objects involved are fixed, as is typical of video games, a priori methods using precomputation can be used to speed up execution.

Pruning is also desirable here, both n-body pruning and pairwise pruning, but the algorithms must take time and the types of motions used in the underlying physical system into consideration.

When it comes to the exact pairwise collision detection, this is highly trajectory dependent, and one almost has to use a numerical root-finding algorithm to compute the instant of impact.

As an example, consider two triangles moving in time  and

and  . At any point in time, the two triangles can be checked for intersection using the twenty planes previously mentioned. However, we can do better, since these twenty planes can all be tracked in time. If

. At any point in time, the two triangles can be checked for intersection using the twenty planes previously mentioned. However, we can do better, since these twenty planes can all be tracked in time. If  is the plane going through points

is the plane going through points  in

in  then there are twenty planes

then there are twenty planes  to track. Each plane needs to be tracked against three vertices, this gives sixty values to track. Using a root finder on these sixty functions produces the exact collision times for the two given triangles and the two given trajectory. We note here that if the trajectories of the vertices are assumed to be linear polynomials in

to track. Each plane needs to be tracked against three vertices, this gives sixty values to track. Using a root finder on these sixty functions produces the exact collision times for the two given triangles and the two given trajectory. We note here that if the trajectories of the vertices are assumed to be linear polynomials in  then the final sixty functions are in fact cubic polynomials, and in this exceptional case, it is possible to locate the exact collision time using the formula for the roots of the cubic. Some numerical analysts suggest that using the formula for the roots of the cubic is not as numerically stable as using a root finder for polynomials.

then the final sixty functions are in fact cubic polynomials, and in this exceptional case, it is possible to locate the exact collision time using the formula for the roots of the cubic. Some numerical analysts suggest that using the formula for the roots of the cubic is not as numerically stable as using a root finder for polynomials.

Spatial partitioning

Alternative algorithms are grouped under the spatial partitioning umbrella, which includes octrees, binary space partitioning (or BSP trees) and other, similar approaches. If one splits space into a number of simple cells, and if two objects can be shown not to be in the same cell, then they need not be checked for intersection. Since BSP trees can be precomputed, that approach is well suited to handling walls and fixed obstacles in games. These algorithms are generally older than the algorithms described above.

Video games

Video games have to split their very limited computing time between several tasks. Despite this resource limit, and the use of relatively primitive collision detection algorithms, programmers have been able to create believable, if inexact, systems for use in games.

For a long time, video games had a very limited number of objects to treat, and so checking all pairs was not a problem. In two-dimensional games, in some cases, the hardware was able to efficiently detect and report overlapping pixels between sprites on the screen. In other cases, simply tiling the screen and binding each sprite into the tiles it overlaps provides sufficient pruning, and for pairwise checks, bounding rectangles or circles are used and deemed sufficiently accurate.

Three dimensional games have used spatial partitioning methods for  -body pruning, and for a long time used one or a few spheres per actual 3D object for pairwise checks. Exact checks are very rare, except in games attempting to simulate reality closely. Even then, exact checks are not necessarily used in all cases.

-body pruning, and for a long time used one or a few spheres per actual 3D object for pairwise checks. Exact checks are very rare, except in games attempting to simulate reality closely. Even then, exact checks are not necessarily used in all cases.

Because games do not need to mimic actual physics, stability is not as much of an issue. Almost all games use a posteriori collision detection, and collisions are often resolved using very simple rules. For instance, if a character becomes embedded in a wall, he might be simply moved back to his last known good location. Some games will calculate the distance the character can move before getting embedded into a wall, and only allow him to move that far.

In many cases for video games, approximating the characters by a point is sufficient for the purpose of collision detection with the environment. In this case, Binary space partitioning trees provide a viable, efficient and simple algorithm for checking if a point is embedded in the scenery or not. Such a data structure can also be used to handle "resting position" situation gracefully when a character is running along the ground. Collisions between characters, and collisions with projectiles and hazards, are treated separately.

A robust simulator is one that will react to any input in a reasonable way. For instance, if we imagine a high speed racecar video game, from one simulation step to the next, it is conceivable that the cars would advance a substantial distance along the race track. If there is a shallow obstacle on the track (such as a brick wall), it is not entirely unlikely that the car will completely leap over it, and this is very undesirable. In other instances, the "fixing" that the a posteriori algorithms require isn't implemented correctly, and characters find themselves embedded in walls, or falling off into a deep void, sometimes referred to as "black hell," "blue hell," or "green hell," depending on the predominant color. These are the hallmarks of a failing collision detection and physical simulation system. Big Rigs: Over the Road Racing is an infamous example of a game which either has a failing collision detection system or does not even have one.

See also

- Hit-testing

- Bounding volume

- Game physics

- Gilbert–Johnson–Keerthi distance algorithm

- Physics engine

- Lubachevsky-Stillinger algorithm

- Ragdoll physics

References

- ^ Ericson, Christer. Real-time Collision Detection. Elsevier, 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Lin, Ming C (1993). Efficient Collision Detection for Animation and Robotics (thesis). University of California, Berkeley. ftp://ftp.cs.unc.edu/pub/users/manocha/PAPERS/COLLISION/thesis.pdf.

External links

- OZCollide Free, Fast and Cross-platform detection library.

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill collision detection research web site

- Prof. Steven Cameron (Oxford University) web site on collision detection

- How to Avoid a Collision by George Beck, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.